Type: Exhibition

Source: Rachel, Peter, Caitlin, John

Annotator: Stacy Boldrick

Sequence: 1 of 5

Year annotated: 2020

Type: Exhibition

Source: Exit, Voice and Loyalty

Annotator: Stacy Boldrick

Sequence: 2 of 5

Year annotated: 2020

The familial dynamic in Rachel, Peter, Caitlin, John extends further in this exhibition. The formal link I see between them lies in the artwork entitled Unsold Editions, six cast glass columns extruded from the shapes of ticket punches. Originally these sculptures were part of an earlier work pairing them with an altered 16mm film in Kenneth, Hilda (2011). At Tramway, the sculptures stood upright in a loose cluster, near the formidable My Terracotta Army, my Red Studio, my Amber Room (2013), with its precisely ordered rows. Unsold Editions features as a collective in this exhibition, but its constituent parts were intended to embark on separate social lives as individual artworks.

The exhibition not only included displaced objects from artworks, artefacts and domestic spaces, it also displaced the viewer, with the entrance replicating Skaer’s corridor to her former studio serving as a threshold and a framing device. Perhaps it is better to think about artworks like Unsold Editions with words like ‘threshold’ and ‘frame’ rather than ‘displace’, with its implied, overdetermined permanent shift from one site to another. Nothing is fixed forever here. When I see Unsold Editions I also see them lying down in Kenneth, Hilda; when I think about Kenneth, Hilda, I think about their iteration at this exhibition, standing up. The possibility for artworks to become fragmented and reconfigured in new forms acknowledges the fact that they have unknown future social lives that their makers can know nothing about.

Type: Exhibition

Source: The Green Man

Annotator: Stacy Boldrick

Sequence: 3 of 5

Year annotated: 2020

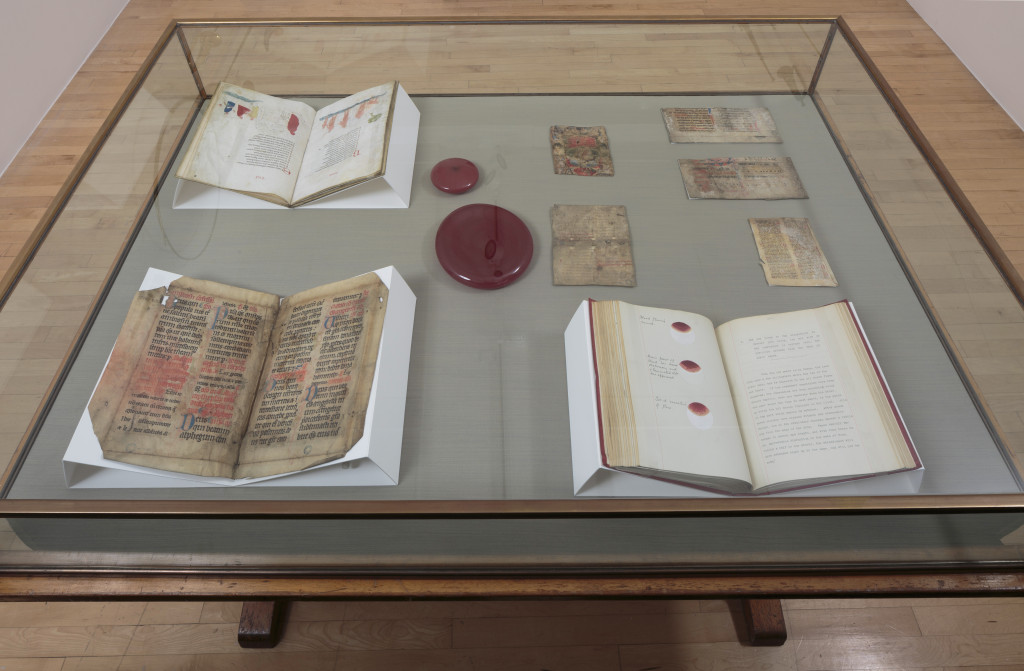

Idolatry, the worship of images, became a problem in Northern Europe when they realised that certain images could hold people in their power. Some images and objects were believed to be able to move and speak as if alive. In the desire to expunge churches of their most dangerous religious objects, sixteenth-century reforms called for their removal and destruction. A visual world was turned upside down. Although in Britain most Catholic religious visual culture was completely lost, some images survived, despite having been defaced, dismantled and displaced. Surviving fragments were hidden, sold or defaced and reused for their materials. Certain religious texts attracted the same fates, and were destroyed, hidden or recycled. Materials that possessed power became categorised as adiaphora, or ‘things indifferent’. Altarpieces became tables, sculptures were cut into masonry blocks for buildings, parchment from religious books became toilet paper. Religious manuscripts were disassembled, cut into rectangular sections and used in bindings for printed books.

Some of these fragments appear in The Green Man, in ‘The Bloody Vitrine’: fragments from a miscellaneous collection called Fragments 211, collected by David Laing (1793–1878), an antiquarian who left half a million items to the University of Edinburgh. The ‘bloodiness’ of this vitrine can be seen in the ink’s liquid nature, as it bleeds beyond its letters on the vellum. They are accompanied by manuscripts concerned with water and blood, a defaced late medieval manual on bathing, Peter of Eboli’s Balneum (1413) and a Master’s thesis entitled Coagulation time of the blood in man: a physiological study (1908). Skaer rescues the otherwise unappreciated fragments to consider them as objects made from liquids, malleable, vulnerable materials. The blood in the vitrine comes not only from liquids but also from the dismemberment of manuscripts, which should always be understood as accompanied by the loss of dissenting human bodies.

Type: Work

Source: Eccentric Boxes

Annotator: Stacy Boldrick

Sequence: 4 of 5

Year annotated: 2020

Actions are as much a part of Skaer’s artworks as the material objects themselves. This image from Eccentric Boxes captures critical, invisible aspects of her work: sources, labour and process. I always imagine but can never fully know the steps in the process of making: how for example in this instance the floorboards of a house move from one site to another, laboriously and painstakingly taken up and removed, then constructed with other materials and to become boxes in a gallery. The part of a house that serves as a stage for activities, absorbing and representing memories and histories, becomes transformed into discrete objects, the opposite of the reception of newly constructed flat-pack furniture into a house.

Type: Exhibition

Source: Leonora

Annotator: Stacy Boldrick

Sequence: 5 of 5

Year annotated: 2020

Finally, all of these threads – anthropomorphism, art agency, materiality, idolatry and iconoclasm and historical memory – come together in the installation Leonora (2007), which includes a film of the surrealist artist Lenora Carrington (1917–2011) and a tropical hardwood table inlaid with Pacific mother-of-pearl featuring Carrington’s hands in silhouette, objects and materials of colonial tyranny. The dialogue between the film and sculpture in the installation is striking. The sculptural element in the installation, Leonora (The Tyrant) (2007), captures as represented in the film the artist’s hands in a moment, gesturing as part of a conversation. In the variegated, luminous surface of this inert sculpture, Carrington’s live gesture lives on, attesting to the vitality of the image, while undermining its ephemerality. I think about Carrington’s response when Skaer asked her about the positive aspects of growing old: ‘Animals, vegetables, minerals, everything dies.’ The object looks back not with eyes that we can see, but with its hands.

Certain images and objects can cast spells on humans. The idea that an image or material object can hold us in its power is bewildering and paradoxical, but it is also an ingrained attitude, a conventional response to particular artworks and artefacts. This seems to me to be a critical thread in Skaer’s work, and is one of several threads informing this pathway. Images and objects sometimes sit in opposition to their materials, limited by their inert properties, and vulnerable to changing physical states and environmental conditions, but the object can also exploit and exalt the materials from which they are made. Rachel, Peter, Caitlin, John embodies some of these ideas, simultaneously attesting to and dismantling the power of images.

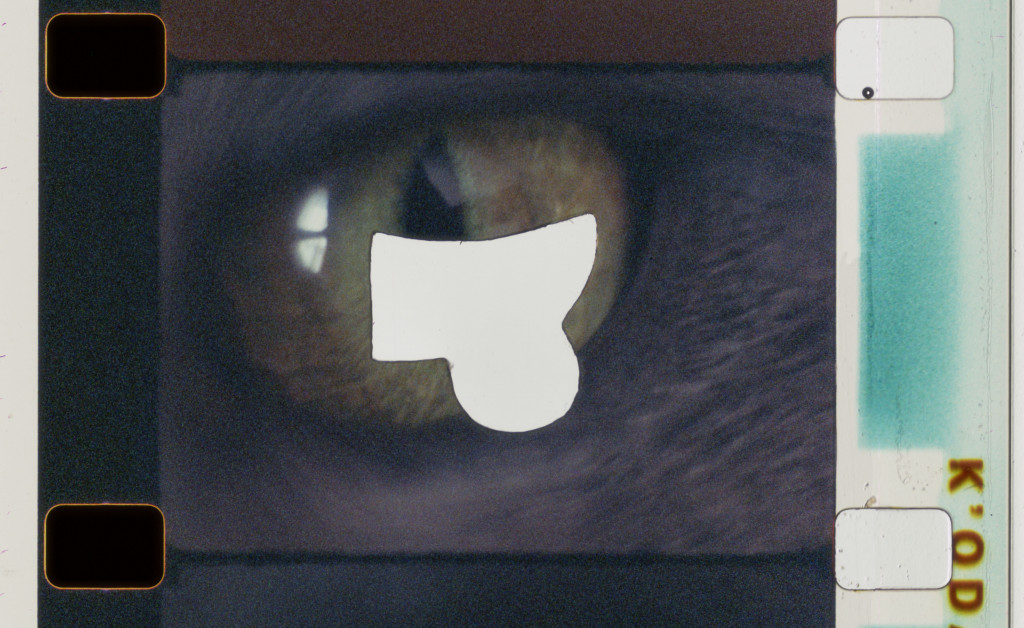

Like its title (full of characters/people), the 16mm films and sculptures in the installation Rachel, Peter, Caitlin, John bring together an unlikely family of images: films of a Rothko painting, the Gutenberg Bible and the eye of a cat are shown next to a table presenting a group of nine abstract sculptures (cast from bronze, copper, pewter, porcelain, plaster and wood). The profile of each sculpture comes from a differently shaped ticket punch (from the Long Island Railway). The film strips themselves are punched, scratched and altered in other ways, so that when projected, small alterations expand and become aesthetic forms in their own right: white light pierces the image, and this absence becomes a compositional element, reminding us it’s an image on a strip of film, not the real thing.

But when we see representations of iconic, rare or recognisable things we sometimes confuse them with the original. The Rothko Chapel in Houston and Rothko paintings have been heralded as transcendent artworks that can move people to tears or unexpectedly resurrect uncontrollable emotions. The Gutenberg Bible changed the world as the first complete printed book made available through mass production, and only 48 copies survive. And cats are among the most popular subjects to view online. The effects of the ruptures and alterations in the Rothko, Gutenberg Bible and cat’s eye all destabilise expectations in different ways, as images bearing a series of physical and visual interventions that appear to negate or diminish them. When viewed collectively as parts of an installation, however these holes and scratches can also be understood as additive, extrusions into the space. The aesthetic and material relationships between the ‘punch’ sculptures and the punched and manipulated film strips are simultaneously antagonistic and collaborative, a skirmish between images and their materials and abstractions and also an expansion of their forms, a paradox. The characters in this artwork are a reverential, referential, visual and material family. It was Rothko who said that an artwork lives and dies through companionship. This one contains multitudes.