Type: Exhibition

Source: Monday 8.4.13...Monday 24.4.13

Annotator: Hope Svenson

Sequence: 1 of 5

Year annotated: 2021

Type: Exhibition

Source: The Good Ship Blank and Ballast

Annotator: Hope Svenson

Sequence: 2 of 5

Year annotated: 2021

My introduction to Lucy’s work was in 2012, when my coworker Robert Snowden showed me the results of a Google image search. Through the cracked glass of the iPhone screen showing a grid of tiny images, I was immediately drawn to a series of block prints the artist made with furniture edges, fragments of new alphabets given form by impressions of the artist’s domestic interior. The mundane dining room chair became an instrument for the potentiality of language. A familiar object of the everyday, its inked impressions made an indecipherable alphabet, teasing the limits of human legibility. The chairs’ hieroglyphic impressions make us recall that language itself is a counterfeit representation of the unknowability of human subjectivity. This theme of language and its forms and fallibilities leaves traces through Lucy’s entire body of work.

Type: Exhibition

Source: A Boat Used as a Vessel

Annotator: Hope Svenson

Sequence: 3 of 5

Year annotated: 2021

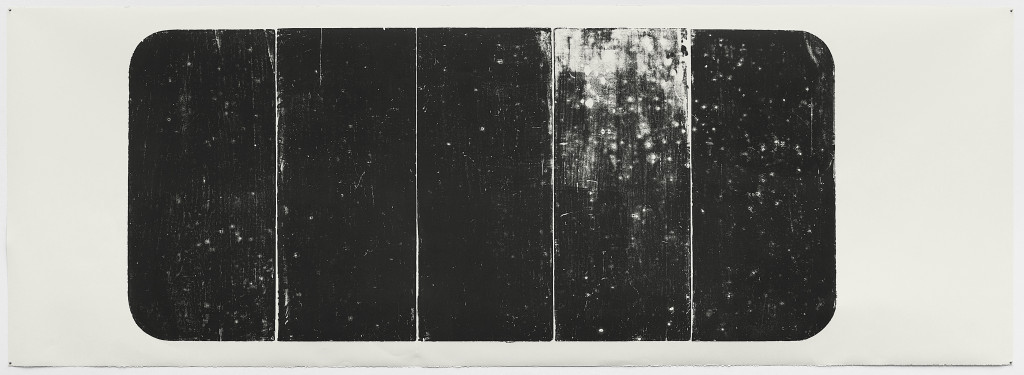

When is a table not a table? A dining room table made into a printing substrate speaks the secret language of its making through its ink impression. The table becomes a sign, but its meaning is just beyond our grasp because the domestic has its own language of interiority, refusing singular interpretation. As a printing substrate, the kitchen table becomes an instrument for evoking family dinners, after school snacks, holiday gatherings, house meetings—a referent as endlessly fluid as it is uniquely personal. The dimensions of space and time are flattened, manipulated into a representation of the moment of encounter, with the print on display acting as a record of the table’s moment of touching and being touched.

Type: Exhibition

Source: Monday 8.4.13...Monday 24.4.13

Annotator: Hope Svenson

Sequence: 4 of 5

Year annotated: 2021

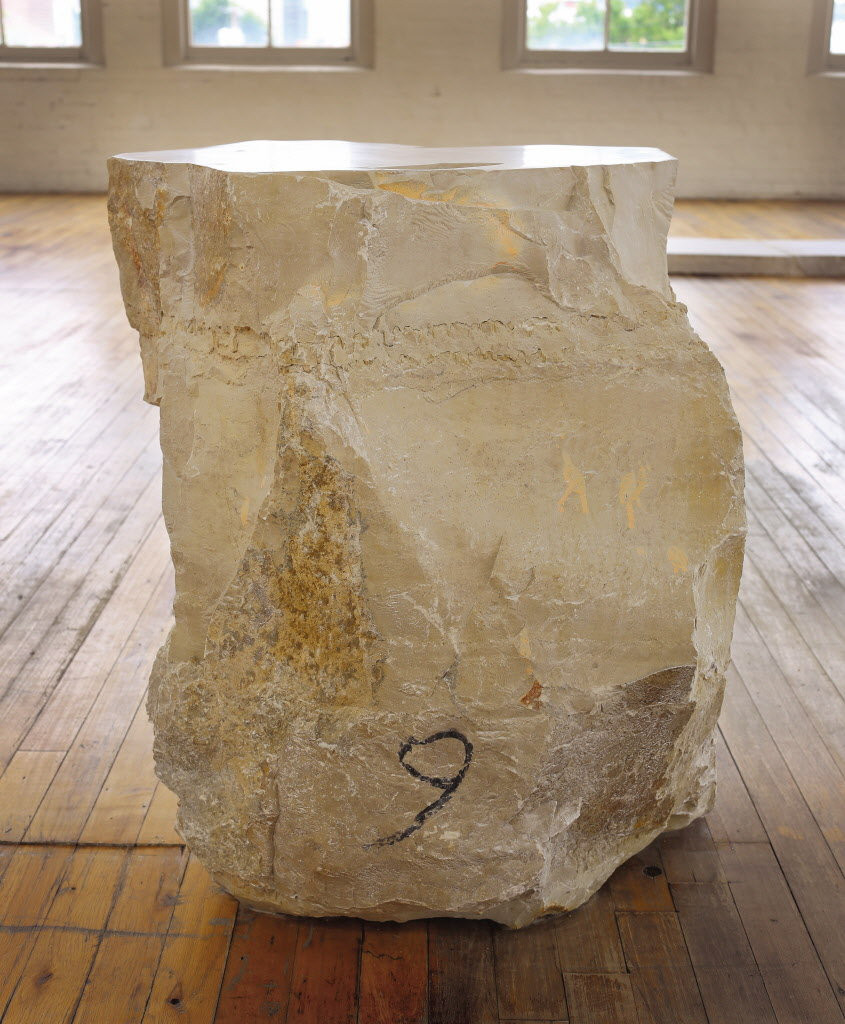

I met Lucy at Jones Quarry, which is located in the traditional territory of the Sioux, and Sac and Fox tribes in the northeastern part of what is now called the state of Iowa. We were there to obtain the raw materials for sculptures that she would produce for exhibition at Yale Union. At the quarry, we signed waivers and donned hard hats and high-visibility vests, then were led through a five-acre boulder field, enclosed by 30 foot sheer limestone ledges. I found two dead rabbits, a raccoon skull, a deer carcass, and at least five piles of coyote shit. We sloshed through ankle deep mud, gray hued from the limestone runoff, following behind an excavator that broke SUV-sized boulders into lounge-chair sized ones that Lucy tagged with orange spray paint if they suited her.

Weeks later, a tractor trailer with eighteen orange-tagged boulders, each weighing between 1,000 and 5,000 lbs., arrived at a stonecutter’s yard on the outskirts of Portland, where the usual fare is granite countertops and marble bathroom tile. An Ogyu diamond-blade wire saw—a room-sized frame maneuvering a taut diamond-studded wire above a motorized conveyor platform—was used to make cuts according to Lucy’s instruction, each cut taking an average of two hours. She made a final selection of five halved and flat-topped boulders to be transported on a flat-bed truck to Yale Union, where we used a combination of gantries, pallet jacks, blocking, chains, and very large men to install the boulders in the gallery space. The installation was a visceral affair: the stomach-churn of riding in the over-capacity freight elevator, and the sickening pop of floorboards straining under the weight of the pallet jack. For the sake of the building’s structural integrity, the stones were aligned on the floor directly above the main north-south support beam, in a delineation of the building’s spine.

Once the boulders were in place, Lucy got to work polishing the rough diamond-cut surfaces not mirror-smooth, but somewhere on the way: buttery to the touch but not shiny. Polishing should have been done outside beforehand, but because of delays and poor planning (mea culpa), it had to be done in the gallery. It looked like this: Lucy with a Makita rotary stone polisher and a hose spraying water for wet grinding; limestone dust and water creating a pervasive whitish slop; me managing tarps and frantically Shop-Vaccing to try to prevent the swill from soaking through the floorboards and dripping into the artists’ studios below. Hours of this left us soaked to the bone with vaporized limestone encasing us in a filmy whitish coating that later dried to a hard crust. Like a kind of anti-Pygmalion, the sculpture itself proclaimed its mute memento mori as it made an attempt to turn its sculptor into stone.

Type: Exhibition

Source: Monday 8.4.13...Monday 24.4.13

Annotator: Hope Svenson

Sequence: 5 of 5

Year annotated: 2021

This work made from the earth asks ancient questions about transformation and designation. In the quarry, there was the stench of dead animals and a foot of standing water; in the gallery, there were white gloves, bubble wrap, and the encircling shroud of language. There is absurdity and brilliance in that alchemical transformation when raw material becomes fine art and enters into a global art market that fuels the excesses of speculators and oligarchs. But most of this alchemy is logistical; these sculptures did not magically spring from the artist’s studio into the gallery. Invisibly, there were millennia of sedimentary pressure forming the fine-grained stone, then there was extraction, transportation, offloading, rendering, and installing. You only saw it once it was insured and its designation as art had been nailed into place, which begs other questions: What happens to the stones two months later when the exhibition gets de-installed? After their momentary stint as art objects with an author and a value, do they get sold back to a concrete producer to be crushed into aggregate and re-enter the industrial realm as raw material? Or do they get shipped to the next art venue and begin circulation in the global art market, into the shady domain of freeports and tax havens? Or maybe they are moved to someone’s backyard to sit there slowly accreting grime and moss, eventually returning to the earth, far removed from their place of origin in the Devonian outcrops of northeastern Iowa.

From the stone henges to the Bird in Space, Lucy self-consciously takes on an art-historical trajectory that begins in the earth and ends in the human realm of power and currency. As much about practical logistics as they are about material histories, Lucy’s stones merge the biological time of human lives and social organizations with the geological time of prehistory and earth-forming. They remind us—like all good art does—that we are alive now and very soon we won’t be.

Lithographic limestone boulders (American Images 1–5) formed the backbone of Lucy Skaer’s exhibition at Yale Union, a show that also featured cast terra cotta multiples, a glass extrusion embedded in the floor, offset prints made from two weeks of front page plates of The Guardian, a cast resin wall enclosure, inlaid mahogany planks, and other carved stone pieces. Because of their heft and mystery, the boulders achieved prominence in the exhibition, anchoring all the other work like a spinal column mooring a body’s extremities. The stones were an archive of the earth—ponderous and silent, but with much to convey about their extraction, their obsolete use value (for printing), their current commodity value (for concrete production), and their temporary performance here as sculpture. Stones talk!

Weighing in at a dense 174 lbs. per cubic foot, lithographic limestone is geologically on its way to becoming marble. Heavy, smooth, and impermeable, it made an ideal printing substrate before tin plate technology was perfected. By not preparing the stones for use as printing blocks but rather leaving them as impossibly heavy boulders with perhaps one surface rendered smooth, Lucy manipulated them just enough to embody the potential of print, withholding the stones’ lithographic utility to hover in the purgatory of potential value. Though the stones carry the burdens of geological and technological histories, they are not objects of nostalgia or talismans of wishing-for. History is invoked but left to its own devices.